The BIS Lunar Spacesuit

- 17th Jul 2019

- Author: Dan Kendall

Right at the beginning of the planning and research phase of our Britain’s Space Race exhibition, we came across a story that we knew we had to tell.

The story of the British Interplanetary Society lunar spacesuit.

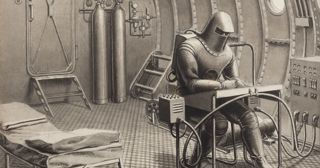

A colleague of mine was flicking through a book on the British Interplanetary Society (BIS), when she saw an incredible picture. It depicted what looked like a mountain climber in a suit of medieval armour (see pic). We immediately knew that we had to make it for real.

The picture had been drawn by Ralph Smith, a member of the BIS – and also their resident artist. Smith used his artistic talents to create images of space concepts that were being worked on by BIS members. However, he would only draw or paint an idea if it had been thoroughly researched and thought through in terms of its engineering and scientific accuracy.

The BIS had been set up in 1933 for like-minded individuals to come together and consider the possibility of interplanetary exploration. Members developed incredibly detailed plans for all sorts of missions into space.

Ideas ranged from satellite launches and planetary space probes, to landing on the Moon and setting up lunar colonies. And this was a talented bunch of people that included the likes of Arthur C Clarke, so, although some of the ideas were a little far-fetched, the BIS was ahead of its time.

The BIS Lunar Spacesuit

In 1939 BIS member Harry Ross headed up a committee looking into the possibility of a mission to the Moon. Unfortunately for him and other BIS members, World War II came along and the organisation disbanded for a while.

Despite the pressing concerns of life during the War, Ross couldn’t help but continue to dream of spaceflight. During this period he began work on the first serious scientific study of what sort of suit would be needed to survive on the surface of the Moon.

When the War was over and the BIS reformed, Ross recruited Ralph Smith to work with him on his lunar spacesuit design. By 1949 the two of them had worked their plans up to a detailed level. In a paper written for the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society, Smith drew representations of a spacesuit designed to be worn in the extreme heat of lunar daytime, as well as the extreme cold of the lunar night.

As can be seen from their schematic diagram, the pair had come up with ingenious systems to cope with the harsh environment found on the Moon. Multilayered textiles kept the wearer in a protective bubble, with pipes supplying oxygen and taking away carbon dioxide. A ‘highly-silvered’ outer layer helped reflect sunlight, whilst a refrigeration system and a cape were involved in trying to regulate the temperature inside the suit.

The spacesuit was particularly bulky, housing an airlock system in the chest. The idea was that the astronaut could retract their arms from the sleeves to open the inner door of the airlock. This gave them the opportunity to pick up rocks, put them inside the airlock from outside the suit and then examine them inside by pulling their arms out of the sleeves. There was enough room to be able to look down inside your helmet to the chest area and inspect what you’d collected. They could even have their sandwiches passed into their suit by connecting the airlock to a lunar base! Even the Apollo astronauts didn’t have that luxury.

What We Did

The first thing we did was find ourselves an expert costume and model maker with a passion for history. Cue Stephen Wisdom. Stephen has made all sorts of high-fidelity models, ranging from U-boats and historic cars, to Apollo spacesuits and World War I fighter planes. And, more importantly, he likes a challenge.

We had the option of showing Stephen Ralph Smith’s designs and getting him to make a model of the suit. But somehow that didn’t feel enough. Instead, we decided to limit him to using only materials and techniques that would have been available to Smith and Ross back in the 1940s. If anything, this only added to Stephen’s excitement to be involved!

So we threw ourselves into research, trawling over all of the work that Smith and Ross had done. Throughout countless phone calls and onsite meetings, we found ourselves going through the process that they would have done if they had actually got to build their suit for real. Stephen and I became the latter-day Smith and Ross.

We couldn’t commit to making a suit that would actually keep you alive on the Moon, but to be fair – their design was flawed in places anyway. It was incredibly well thought out, but it couldn’t have done what NASA’s Apollo spacesuits did.

Nonetheless, as we refined ideas, and Stephen went away and manufactured test pieces and templates (and even a delightful plasticine model), we found ourselves continuing the research of Smith and Ross. We had to work out in the real world what would and, more importantly, wouldn’t have worked.

This led to Stephen finding himself in what would be an unusual situation for most people, but is probably just another day for him!

Research, Development, and Getting Struck

By this stage, Stephen had built the basic suit and could now actually try it on. Which is how he ended up inside the suit at ten-thirty in the evening, ready to carry out some testing.

He wanted to see how the shape was coming together and had both his arms inside the suit in the attached gloves. According to Ross and Smith’s designs, it should be possible to extract your arms and move them into the chest area.

However, with tight-fitting gloves, getting your hands out of the sleeves proved quite problematic. In fact, Stephen found himself more than a little stuck. On his own, he faced the prospect that he might actually have to wake up his neighbours to help him out of the suit.

When I found out I couldn’t help but laugh – especially knowing that he had eventually found his way out. Imagine what sight would have met his neighbours if they’d opened their door, only to a find a 1940s spaceman stood outside!

After a lot of revisions and tweaks – we realised that we could only redevelop the suit so much before we lost the sense of the original designs.

Ross and Smith had based a lot of their thinking on 1940s diving suit technology, so this formed the basis for a lot of what Stephen created.

Calling in favours and expertise from a network of craftspeople, the suit started to take shape.

The beautiful backpack that he made even involved welding that was carried out by a member of the Williams Formula 1 racing team!

The Big Reveal

Throughout the process, most of my contact had been through phone calls and photos. Therefore, when Stephen said he was ready to deliver, I found myself feeling a little nervous.

What if I wasn’t happy with it? So much work had gone into it – quite possibly blood, sweat, and tears. What if it didn’t fit inside its display case?

I was confident in Stephen’s ability but had only seen snapshots of the project. An unpainted helmet here, disassembled moon-boots there. I could see the basic components and how they would fit together, but it was a leap of the imagination to think of the whole suit as one.

There was, of course, no need to worry. When it finally arrived, it looked amazing. This was, and still is, the first accurate full-scale model of Ross and Smith’s plans. And it is a showstopper.

Whilst sadly neither man is still around to see it, I honestly believe they would have been delighted by what Stephen has made. I’m certain they would have been just as pleased as I am.

And no doubt they would have had just as much fun as we did thinking through the problems of making a lunar spacesuit for real!

The Surface of the Moon

Once it went on display, there was one final finishing touch that we felt was necessary. We needed a lunar surface to make it really look the part.

But how do you recreate the fine lunar soil – the dust like surface experienced by the Apollo moonwalkers?

Answer – cat litter.

Ever ingenious, our Head of Exhibition and Design came up with this novel recipe:

- Take some ordinary cat litter – preferably unused

- Put it into a blender – preferably not the one in the staff kitchen

- Blend to a fine dust and sieve into the base of a display case

The suit can now be seen in the Rocket Tower, within the Britain’s Space Race exhibition. And, as I look at it standing on a cat-litter lunar surface, I can’t help feeling this has been one of the weirdest – yet most enjoyable – projects that I’ve ever worked on.

About the author: Dan Kendall is the Curator at the National Space Centre.